PLAY OF HANDS (Juego de Manos), the exhibit by artist Manuel Londoño Mejía at MAJA (Museum of Anthropology and Art of Jericó, Antioquia), December 3rd, 2022- January 28th 2023. Manuel Londoño Mejía’s art exhibit Juego de Manos (Play of Hands) welcomes the viewer with two large monochromatic hands, one blue and one red, carefully drawn…

PLAY OF HANDS (Juego de Manos)

PLAY OF HANDS (Juego de Manos), the exhibit by artist Manuel Londoño Mejía at MAJA (Museum of Anthropology and Art of Jericó, Antioquia), December 3rd, 2022- January 28th 2023.

Manuel Londoño Mejía’s art exhibit Juego de Manos (Play of Hands) welcomes the viewer with two large monochromatic hands, one blue and one red, carefully drawn in colored pencils. Their gesture is expressive: one hand takes, the other gives. The play of hands in the original Spanish title is suggestive of the ability to make objects appear and disappear, as if by magic; the title could also be translated as sleight of hand. The play in question can refer as well to juggling, in turn in its various senses of skillfully keeping multiple objects in the air while catching others, or adroitly balancing multiple challenging tasks. Here, in the strikingly beautiful space of the MAJA, the artist’s exhibit indeed juggles images. Pencil lines perform magic and images declaim their own kind of poetry, saying what cannot be said with words.

Play of Hands

Play of Hands

Manuel starts his account of his exhibit by reminding me of art historian W.J.T. Mitchell’s injunction to ask pictures what they want. Manuel adds: “Images then throw the question right back at us.” I am not persuaded that images indeed turn the question back on us, but certainly, in this exhibit, the viewer feels that the images are proffering answers, and that they speak of games, alchemy, desires, and encounters. Manuel has taught the art of drawing, and it is clear that with his artwork, he has answered his questions about aesthetics.

Manuel’s drawings are respectful of the drawn line, but rather than letting it be straightforward and speak on its own, they multiply it, superpose it, inject movement into it. Manuel does not erase or smudge; rather, he reserves the white spaces on the paper with artful skill, leaving them clean and untouched, free even of the lightest tones of other colors. Volume, light, and shadows emerge from this. Each element is wrought out of a single color. At times, an image comprises three elements—say, a hand, a flower, and a leaf—and each of these is drawn in a single color. It is not that he uses three hues of blue on a blue element; no, with one single blue color pencil he resolves the challenge of representing and signifying. Of course, to represent requires choices regarding visual verisimilitude, but other decisions also impinge greatly on communication: the sizing of elements within the frame of representation, position, light, lighting, volume, weight, equilibrium, etc. The monotone of the works brings to mind pictures in old encyclopedias, whose simple, delicate, and careful diagramming, Manuel readily confirms, attract him intimately.

The titles of works of art have mattered in the history of art. Titles suggest, elicit, and compel, and they create expectations. Expectations are fundamental to perception, because we tend to see what we expect to see—something designers know well. A title can be an hors d’oeuvre, complete an image, contradict it, reinforce it, or dilute it. Manuel’s titles fulfil these functions.

En sus brazos caben muchas lunas (Its branches embrace many moons), centers on a branching, leafy tree drawn with mastery. Manuel works unhurriedly, seduced by nature’s processes and emulating them, allowing the drawing to grow organically, even botanically, branch by branch and leaf by leaf, caressing the paper with color, like a gentle breeze in the leaves. His lines are subtle; they do not tear, damage or break the surface. Sparing in this case as in all his work, he wittingly selects but a few tools from the inventory of techniques and strategies available to the skillful artist, and with it achieves his designs.

Its branches embrace many moons

Its branches embrace many moons

Atrapasueños (Dreamcatcher). The title corresponds to a parade of images. In one of these, a pair of hands hold flowers; in another, paper cutout silhouettes are camouflaged within the background. Manuel cannot easily recall his dreams, but yet he wishes he could hold on to them. Hence the title and hence his invention—or is it his capture? —of dream images.

Something in Manuel’s loving work reminds me of the film El sol del membrillo (Dream of Light), in which director Víctor Erice filmed Spanish artist Antonio López García’s method of work. Filming began the 29th of September of 1990, and focused on how López García labored to capture the season’s sun and its effects on the quince tree in his garden, before the fruits ripened and fell. Perhaps Manuel’s work reminded me of this film because both share dreams, a certain sense of the real, and devotion to beauty and serenity.

Dreamcatcher

Dreamcatcher

Another title reads Dime el camino para despertar (Tell me how to awaken). The piece features an owl drawn with charcoal on a piece of cloth reminiscent, on many grounds, of a shroud. The title is of such importance that the artist sewed it in white thread on the white cloth. This work has a subtle relation to religious icons. In his art, Manuel seeks to spark an efficacious connection between ritual and magic.

Tell me how to awaken

Tell me how to awaken

In Lago dormido (Dormant Lake), the silhouetted profile of a boy is a window through which water can be contemplated, or perhaps the lake is a head; interpretation is left to the eye of the beholder.

Forma de nube (The Shape of a Cloud) is fashioned on paper made of fiber from the fique plant (Furcraea andina), which resists being drawn on. But Manuel applies dry pastel to it, saturating the paper with blue. The paper’s surface frays and takes on the appearance of animal fur, and the artwork deliberately becomes ambiguous, somewhere between faunal and ethereal.

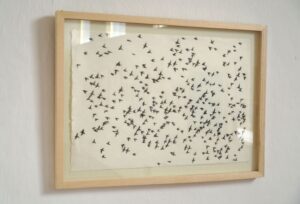

In 393, there are 393 birds drawn with charcoal on Japanese washi paper. The flock flutters and plays in the air in different directions, but each bird is unique and very carefully drawn, with delicate light making the edges of its wings translucent. The effect is extraordinary.

393

393

Other titles are Ludus amoris, Signo de fuego (Sign of Fire), Cripsis (Crypsis), Antes uno, ahora otro (One Before, Now an Other), Poema de los átomos (Poem of the Atoms).

A strong point of the exhibit is a dialogue with nature. The artist seeks to mediate between natural life and human life, fostering a dialogue that arouses wonderment.

“The sheer number of decisions that an artistic process demands can be a source of anguish,” says Manuel, who for that very reason readily allows his artwork to be nourished by the contingent and unexpected, by that which is beyond his control. Somewhere between a strategy and an accident, exposure to sunlight tans his paper and gives it a darker tone, while parts unexposed remain their original color. Manuel also repairs with gold leaf the accidental scratches and tears on paper, as in the Japanese Kintsugi or Kintsukuroi technique to restore broken ceramics. The effect, here like in the Orient, is to highlight each work’s uniqueness and history, and thereby to augment its worth.

One Before, Now an Other

One Before, Now an Other

Manuel’s drawings easily rise from two-dimensional flatness to three dimensions. They do just this in several pieces of the exhibit, such as in Butes, where a gymnast leaps from every fold of a hand fan. The drawing occupies volume and space, now that its paper surface, formerly flat, folds and unfolds.

Lengua de pájaro (Language of the Birds), is a light box, the drawings on its screen transferred with carbon film. Manuel says that everything happens in the imagination. Looking upon this light box, I believe him.

Language of the Birds

Language of the Birds

Totem is a sculpture composed of four cubes, all six sides of which feature drawings. They are stacked one atop of the other. The cube at the base alludes to the earth, the upper one to the sky. They are displayed in a glass dome.

El enamorado (The Lover). This tapestry is woven out of virgin lambswool. Manuel picked feathers of many different shapes, colors, and sizes in his walks. Each feather is conjoined with beeswax and fine silver laminate to a cactus or corozo palm spine, transforming it into a dart that embeds itself in the tapestry. The spines are Eros’s arrows, the feathers are life and liberty, and the fleece is Manuel’s own skin. Or so I see it—my subjective take after conversing with Manuel.

Manuel’s work is coherent. Each image situates itself in the space of imagination, a fact that can be grasped easily in the very forms of representation that he has chosen. Poetry, exquisite delicacy, and the love of objects hold sway in this exhibit. The images in Manuel Londoño Mejía’s artwork flow as serenely as his mental processes do. There is notable consistency—I want to call it an identity—in his life, his intellectual processes, and his artistic work.

Traducción al inglés por Carlos David Londoño.

Comparte tu opinión

Buscar en Blogs

Blogueros notables

Mas votados

Todos los Blogueros

- CastroOpina

Por @castroopina

- Los que sobran

Por @Cielo _Rusinque

- Coma Cuento: cocina sin enredos

Por @ComíCuento

- Tenis al revés

Por @JuanDiegoR

- A calzón quitao

Por A calzón Quitao

- La Guía Astral

Por ACA

- Lloronas de abril

- El Peatón

Por Albeiro Guiral

- Unidad Investigativa

Por Alberto Donadio

- Detrás de Interbolsa

Por Alberto Donadio

- Alejandro Pinto

Por Alejandro Pinto

- Cura de reposo

- ¿Se lo explico con plastilina?

Por alter eddie

- Un Blog para colorear

Por Alvaro J Tirado

- Voces por el Ambiente

- Catrecillo

- Relaciona2

Por ANDREA VILLATE

- Zona Mixta

- Bike The Way

Por Andrés Núñez

- Ventiundedos

- El invitado

Por antojarcu

- Ese extraño oficio llamado Diplomacia

- La tortuga y el patonejo

Por Baba

- Bajolamanga.co

Por Bajolamanga

- 300 GOTAS

Por Bastián Baena

- Con-versaciones

Por Bat&Man

- Corazón de mango

- Mi Opinión

Por Ben Bustillo

- Bernardo Congote

Por Bernardo Congote

- El Hilo de Ariadna

- El Río

Por Blog El Río

- Un Punto de Cruz

Por buscobeca.com

- Mirabilia

- Cara o Sello

Por Caraoselloblog

- Dirección única

- Media & Marketing

Por Carlos Castillo

- Hundiendo teclas

- Colegio de Estudios Superiores de Administración

Por CESA

- La Sinfonía del Pedal

- Follamos, luego existimos

- Colirio

Por colirio

- Colombia de una

Por colombiadeuna

- El Mal Economista

Por columnistas eme

- Palabra Maestra

- Olas y Ecos

Por dafevid

- Mercadeando

- Filosofía y coyuntura

- En contra

Por Daniel Ferreira

- Claudia Palacio

- De Sexo Hablemos

Por desexohablemos

- De ti habla la historia

- Plétora

- Las palabras y las cosas

Por Diego Aretz

- Yo veo

- Tejiendo Naufragios

Por Diego Niño

- Líneas de arena

- Desde la Academia

Por Economia

- Destellos de un mundo en mutación

- It was born in England

Por Eduardo Ustáriz

- Cuestión digital

Por Edwin Bohórquez

- El Mal Economista

- El MERIDIANO 82

Por El meridiano 82

- ESTADO DE COMA

Por Eliana Samacá

- El Magazín

Por elmagazin

- La vaca esférica

Por eltrinador

- El Mal Economista

Por EME

- Otro mundo es posible

Por Enrique Patiño

- Actualidad

- Gramófono cultural

- Tolima-Tolimán

Por FabiolaH

- La agenda del CFO

Por Felipe Jánica

- Dos o tres cosas que sé de cine

Por fgonzalezse

- República de colores

- Más que fotos

Por Gabriel Aponte

- La Franja De Gaso

Por Gaso

- cafeliterario.co

- Embrollo del Desarrollo

Por Gudynas Eduardo

- Hernán González R

- Calicanto

- Humedales Bogotá

Por humedalesbogota

- Ecuaciones de opinión

- Internet pa’l diario

- El bosque es vida- IRI Colombia

Por IRI Colombia

- Meditaciones Absurdas

- Deporte en letras

Por Iván Gutiérrez

- Pazifico, cultura y más

- Conversar, Sentir y Pensar…. Desde el SUR

- Parsimonia

Por Jarne

- Ciudad Sostenible

Por Jen Valentino

- Más allá de la medicina

Por jgorthos

- George o nomics

Por Jorge Borrero

- La droga, ¿y Colombia?

Por Jorge Colombo*

- Hypomnémata

- Si yo fuera

- Utopeando │@soyjuanctorres

- Minería sin escape

- Políticamente insurrecto

- Cosmopolita

- Inevitable

- En segunda fila

- Actualidad

- AdverGlitch

- Sobrevivir a la Edad Media

- A la Palestra

- Ready player number two

Por JuanDLink

- lado oculto radio

Por ladoocultoradio

- La revolución personal

- Las Ciencias Sociales Hoy

- Ciencia para el buen vivir

- Liarte: diálogo sobre arte

- Una habitación digital propia

- Los perdidos

Por losperdidos

- En jaque

- Reencuadres

Por Manuel J Bolívar

- Putamente libre – Feminismo Artesanal

Por Mar Candela

- LA CASA ENCENDIDA

- Psicoterapia y otras Posibilidades

Por María Clara Ruiz

- Política

Por Maria MesaR

- Bienestar en tiempos de drones

Por Maria Pasión

- Desde el fogón

Por Maritornes

- Consideraciones políticas

Por Maylor Caicedo

- Ella es la Historia

Por Milanas Baena

- Mongabay Latam

Por Mongabay Latam

- Ojo de pez

Por Mónica Diago

- Nadimcomics

Por nadimcomics

- NTT DATA: Tendencias disruptivas y nuevos modelos

- Con los pies en la tierra

- Tributos y Atributos

Por OSWALDO PEÑA

- El telescopio

Por Pablo de Narváez

- PauLab Laboratorio Digital / Un clic hace la diferencia

- El Último Verso

Por pavelstev

- Lloviendo y haciendo sol

Por Pilar Posada S.

- Esto mejora, pero no cambia

- El poder de la tecnología: Cómo nos cambia

Por Rafa Orduz

- La conspiración del olvido

- Don Ramón, psicología laboral

Por ramon_chaux

- Coyuntura Política

- Corazón de Pantaleón

Por ricardobada

- Reflexiones

Por RicardoGarcia

- DELOGA BRUSTO

- Apuntes de Ciencia

Por Santiago Franco

- La Acción Política de Educarse

Por Santiago Muñoz

- La Perla

Por Sebastián Gómez

- Óscar Sevillano

Por Sevillano

- Solteras DeBotas

Por Solteras DeBotas

- La cuestión animal

Por Steven Navarrete

- Tareas no hechas

Por tareasnohechas

- Tíbet de Suramérica

- El Cuento

- Blog de notas

Por Vicente Pérez

- El Blog del Cerebro

- Derecho para todos

- Conspirando por un mundo mejor

Blogueros de la Semana

Los editores de los blogs son los únicos responsables por las opiniones, contenidos, y en general por todas las entradas de información que deposite en el mismo. Elespectador.com no se hará responsable de ninguna acción legal producto de un mal uso de los espacios ofrecidos. Si considera que el editor de un blog está poniendo un contenido que represente un abuso, contáctenos.